We had a very special guest – arguably the most special guest you can host on a German tennis court: Boris Becker stopped by to shoot a commercial in our new three-court arena. What it’s like to meet a legend.

Text and photos: Ferdinand Dyck

At exactly 10 a.m. on a Tuesday in mid-November, Boris Becker is sitting in the boardroom of the Treptower Teufel tennis club, having his face made up. Just to be clear: Boris Becker. Treptower Teufel. Boardroom. Yes, you read that right.

The table where members usually leave their racquets for restringing has been taken over by a makeup artist, who is applying a solid layer of foundation to the face of Germany’s greatest male tennis player of all time. Becker, screened off behind a folding wall, is being prepared for a commercial he will shoot moments later in our indoor hard-court arena.

How this came to be is mostly the result of coincidence. The shoot was originally planned for Milan, where Becker lives. Then, at short notice, the production was moved 840 kilometers north, to Berlin. Why remains mostly unclear. The production manager suspects, “It probably just suited Boris better.”

The crew googled “tennis hall Berlin” and, by chance, the top result was our club. A few emails later, a black van collected the three-time Wimbledon champion from a luxury hotel in Charlottenburg and ferried him to the Willi-Sänger-Sportanlage.

At the entrance, cases, tables, and lighting crates were already stacked. On Court 11 — the one facing Court 8 — the miniature set was ready: two giant lamps, a few umbrellas, cameras on tripods. Not much scenery required. After all, today, we are the scenery.

The shoot itself unfolds as unspectacularly as a commercial shoot probably should be. At the start, the leaf blowers on Köpenicker Landstraße briefly test the patience of the sound engineer, but soon Becker begins three hours of repeating short English lines to camera and microphone — memorize, perform, repeat. What exactly he is saying, and what product it is for, is strictly confidential. And, more importantly, beside the point. Much more interesting? Watching Boris.

How he strolls alone across the empty courts, reading the next line off a small sheet of paper, murmuring it to himself. You can easily spot he has done this for decades. The famous AOL commercial — “Bin ich da schon drin oder was?” — aired 26 years ago. His gait, however, is not as springy as it used to be. Becker is limping — the hip.

Or watching him stand before the camera, hands folded loosely at his waist. Anyone who has ever seen German Eurosport coverage knows the pose. His face blank at first, and then — on cue — the famous half-mischievous smile: charming around the mouth, weary around eyes that blink more deeply than they used to.

He takes in everything: the cameras, the crew, the room, and me — when I first enter the hall. He doesn’t appear to be particularly curious but he studies me for a few beats, filing me somewhere in his mind. Mostly, he keeps an eye on the time. When work moves slowly, he quietly assumes control. “So, that was good,” he declares after one take. “A little faster, please,” he commands before another.

What strikes everyone is how serious he is. Serious, and unreachable. When he throws the beige-colored coat over his shoulders to grab a breath of fresh air, he avoids eye contact on the way to the door. When someone on set cracks a joke, he doesn’t smile. In the end, not many jokes are cracked.

Someone asks whether he might have time for a quick selfie while waiting for the next shot. Becker cuts him off: “We’re working now. Job comes first. Maybe later.” It doesn’t sound unfriendly. But it doesn’t sound friendly either.

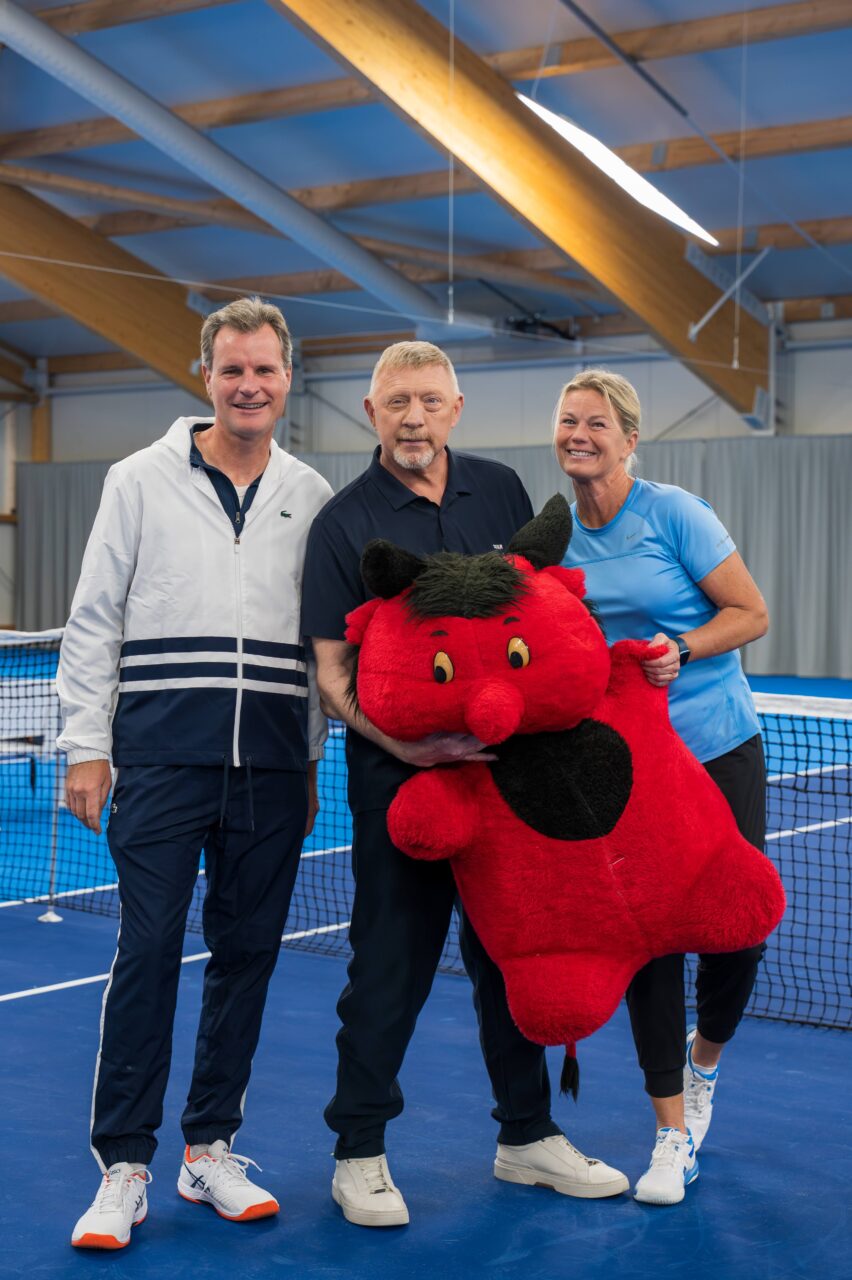

He seems happiest the moment he’s handed the racquet. The crew had picked up a sleek €600 model somewhere in Berlin and got it strung with natural gut — at least that’s the preferred version of the story circulating on set. He hits a few forehands and backhands with Silke, our club coach. He even smiles a few times — while the cameras are not yet rolling, that is.

“So, now volleys,” he says, with the natural authority of a man who has coached the very best. The man who ten years ago explained to Novak Djokovic why showing up at the net from time to time might not be a terrible idea. Who, most recently, worked with Holger Rune. And who is constantly rumored as a potential coach for Alexander Zverev.

On court, Becker drifts into the director’s role almost naturally. He positions the camera, adjusts the progress of the shot. After ten minutes, he announces: “So, that’s it, right?” When I take the group photo at the end — crew members and club officials at the net — he is already signaling me to hurry before everyone has even gathered.

Later, I will spend a long time thinking about what this brief encounter revealed about a man I have felt familiar with since childhood. I didn’t idolize him during his playing days — I fell in love with tennis only at the end of his career — but over the years my respect for him constantly grew.

Because he says pretty smart things about tennis. Because he remains, despite enough setbacks for several lives, a man who keeps going — unshaken. Because less than three years after serving time in an English prison, he is again successful, again ubiquitous, again the most important voice in German tennis, with a bestselling book and a thriving podcast.

But the real realization was this: I do not know Boris Becker at all. I had imagined him warmer, more accessible, I expected him to be – yes – a little nicer. And perhaps I understood one thing while watching him in our brand-new hall: he seems to no longer care whether Germans love him — not even those who happen to play tennis in Treptow.

Recently, he chastised the Italian press after they criticized Jannik Sinner for skipping the Davis Cup final. In an interview with Corriere della Sera, Becker said: “Jannik Sinner does not belong to Italy. Jannik Sinner belongs only to Jannik Sinner.”

To me, that sentence is a clue. Becker has lived, since his first Wimbledon title forty years ago, what Sinner is now beginning to face: that every person, at least every German person who crosses his path, feels entitled to a piece of him. A selfie. An autograph. A quip. A grin. And Becker — at least now — seems to disagree on that.

To be clear: not once in Treptow did he behave badly. He never raised his voice, never embarrassed anyone, never even looked irritated. He was a consummate professional — and that professionalism included distance. That fans who once stayed up all night to watch him win a match in Melbourne and New York might hope for a little more is understandable. That people hope for the same thing every single day, wherever he goes, is easy to forget.

After graciously giving us five minutes for a few questions for the club newsletter, the most prominent guest Treptower Teufel have ever welcomed climbs into a car at 2:30 p.m. and heads for the airport. Where he’s off to? Again, nobody seems entirely sure. I suspect he is quite alright with that.

“Hard courts are a bit tougher on the body”

We met Boris Becker for a world-exclusive interview: The six-time Grand Slam champion talks about our new indoor hard-court facility, mental strength – and the comeback of the volley.

Boris Becker, welcome to Treptower Teufel Tennis Club.

Thank you very much.

You missed the official opening of our new hard-court arena by just one day, but you were one of the first to play in it. What do you think?

It looks great. Honestly, I didn’t expect something like this in Treptow. It’s a fantastic three-court hall, and the surface is excellent – what is it, Rebound Ace?

It has a slightly different name, but basically it’s Rebound Ace, yes.

That’s good. We play half the year indoors because of the weather and the long winter, so having a good hall is essential.

A lot of our members have never played on a hard court, only on clay. You’ve won three Grand Slams on hard court – once in New York, twice in Melbourne. Any tips?

Hard courts are a bit tougher on the body. You need to make sure your knees, hips and ankles are properly warmed up. In a way it’s easier than clay though, because the ball bounces cleanly – on clay you sometimes get bad bounces. So it’s a great surface, but physically a bit more demanding.

Footwork is important, isn’t it?

Yes. The bounce is a little higher and probably a bit faster than on clay. But overall, hard court is a very good surface for tennis.

Let’s go back to another indoor arena. Twenty-nine years ago: Hannover, ATP Finals, Becker vs. Sampras. We recently watched all five sets again with the team – an incredible match! What really stood out to us was the absolute focus on both sides. No tantrums, for hours, not even a look at the coach. Is that the better way – compared to the emotional displays we often see from players today?

I think a mixture is best. You have to stay focused – in our case it was over five sets. Today at the ATP Finals they only play best of three, so matches are won and lost more quickly – which makes mental discipline even more important. And of course there is always communication with the coach, and sometimes emotion if you hit a great shot – or a bad one. But you have to manage your energy, that’s the key: if you get too emotional, you burn out too fast.

We’re standing here on the terrace above our clay courts – where sometimes you can see some rackets fly. Dramatic meltdowns are quite common in amateur tennis. Do you have a trick for keeping the nerves? In your new book “Inside” you talk about discovering Stoicism.

I didn’t really discover it recently. If you watched that Hannover final – those five sets – that was Stoicism on a tennis court. I was already doing that back then. You have to try to stay focused and only control what you can control. You can control your emotions and your thoughts, not those of your opponent.

Is there a trick – maybe looking up at the sky to reset?

It’s mostly common sense. Even in this interview, I can’t control what you ask me – only what happens in my head and what comes out of my mouth.

You’re one of the greatest volley players of all time. But in Germany, at least nowadays, the net has become almost a no-go zone in amateur tennis. You’ve also urged some top German players to be more aggressive. Was coming to the net simply more common in your era, or did you have a coach who emphasized it especially?

It was more common to go to the net. Although if you watched the ATP Finals in Turin, you’ll see that Alcaraz is now at the net more often than two or three years ago – same with Sinner. I think the game is shifting again. Players are rediscovering the net, and also the serve. There was a period when the serve wasn’t given as much importance. But to be a complete player, you have to feel comfortable at the net as well.

Since you brought it up: let’s go back to one more indoor arena – in Turin. You’ve just returned from the ATP Finals there. Do you share the impression that Carlos Alcaraz always seems a bit unhappy indoors in winter – a bit less joyful than he does outside in the sun?

He played very well this time, he’s reached maybe the best indoor form of his career. But right now, Sinner is almost unbeatable indoors. Alcaraz has had his best season overall and rightly finished the year as world number one – but only by a very slim margin ahead of Jannik Sinner.